Lab experiments with saltwater solutions have provided researchers with a range of temperatures where water remains liquid under icy world conditions.

By Beth Johnson

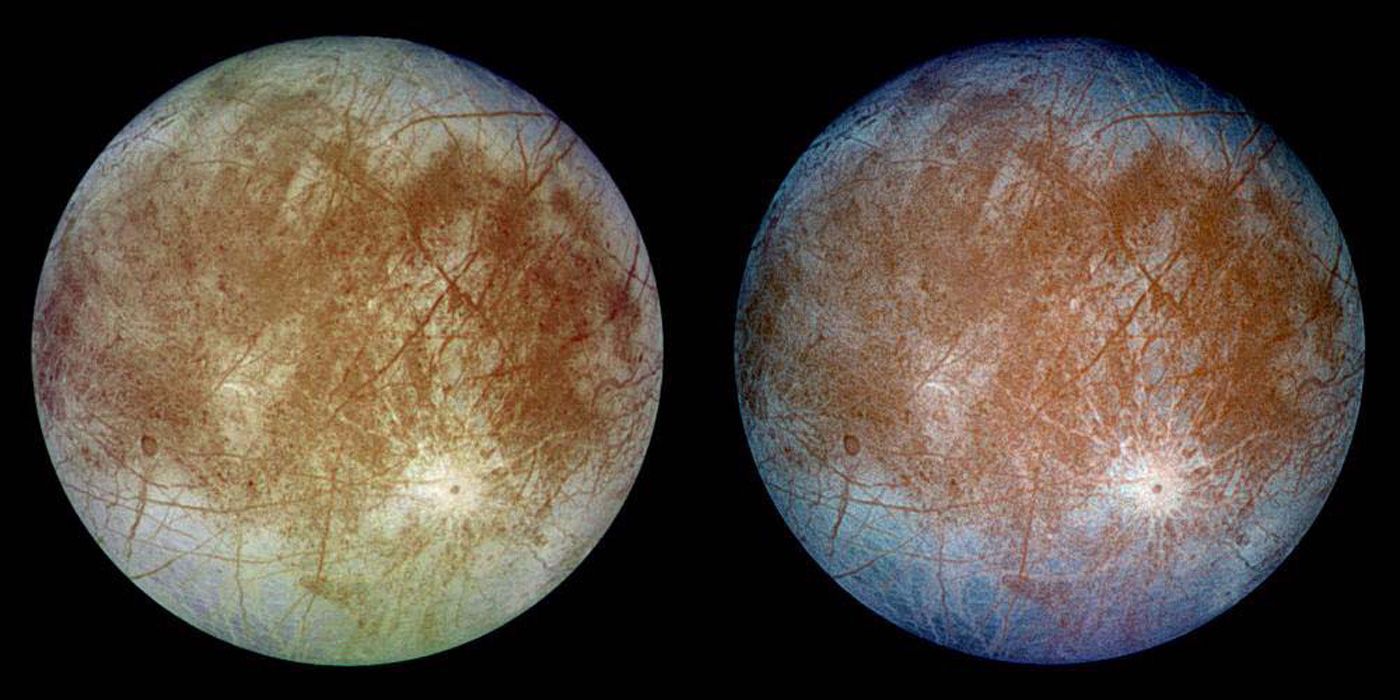

We’ve written before about icy worlds in our solar system and how they have liquid water under those icy shells. These worlds include the likes of Europa, Ganymede, Titan, and Enceladus, and it turns out that they make Earth look dry.

Now, in a new paper published in the journal Cell Reports Physical Sciences, a team of researchers has provided possible temperature ranges for keeping all that water in its liquid form. That’s sort of key for developing life beneath the surface, after all. Co-author Baptiste Journaux explains: The more a liquid is stable, the more promising it is for habitability. Our results show that the cold, salty, high-pressure liquids found in the deep ocean of other planets’ moons can remain liquid to a much cooler temperature than they would at lower pressures. This extends the range of possible habitats on icy moons and will allow us to pinpoint where we should look for biosignatures or signs of life.Z

The team ran experiments to find just where the lowest temperature of various saltwater solutions was where the solution was still liquid. Saltwater can stay liquid at lower temperatures, as those of you living in places with winter and snow and ice can attest to every time you sprinkle salt on your driveway. On top of using salty solutions, the experiments upped the atmospheric pressure to 300 megapascals — about three times the pressure found in the Marianas trench.

It turns out that increasing the pressure is more important than changing up the mixture, as the lowest possible temperature shifted similarly across the different solutions. Co-author and team lead Matthew Powell-Palm explains: This similarity further revealed that the response to pressure of the minimum temperature for a liquid to exist is mainly controlled by the ice and is relatively insensitive to the behavior of the other solid salt phase. This provides an invaluable and fundamental rule-of-thumb for future compositional modeling of different solutes and solutions: The pressure dependence of the [minimum] temperature may be roughly approximated by the pressure dependence of the melting point of pure ice.

With so many missions scheduled to head to these icy worlds in the next decade or so, we may soon have a chance to test these results in situ with landers and probes. We’ll keep you all up-to-date on those missions as they happen.

More Information

UC Berkeley press release

University of Washington press release

“On the pressure dependence of salty aqueous eutectics,” Brooke Change et al., 2022 April 12, Cell Reports Physical Science

This story was written for the Daily Space podcast/YouTube series. Want more news from myself, Dr. Pamela Gay, and Erik Madaus? Check out DailySpace.org.

This article was originally published by Beth Johnson on medium.com.