An experiment conducted in Alaska used long-wavelength radio transmissions to hopefully map the mass distribution of a potentially hazardous asteroid.

From the high peaks of the Andes to the deep cold of the Arctic and Antarctic, space science happens in some amazing locales. The dry air, often clear skies, lack of surrounding buildings, and little light pollution help with any number of observations. Last week, one particular experiment wrapped up for the High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program, or HAARP, located in Gakona, Alaska.

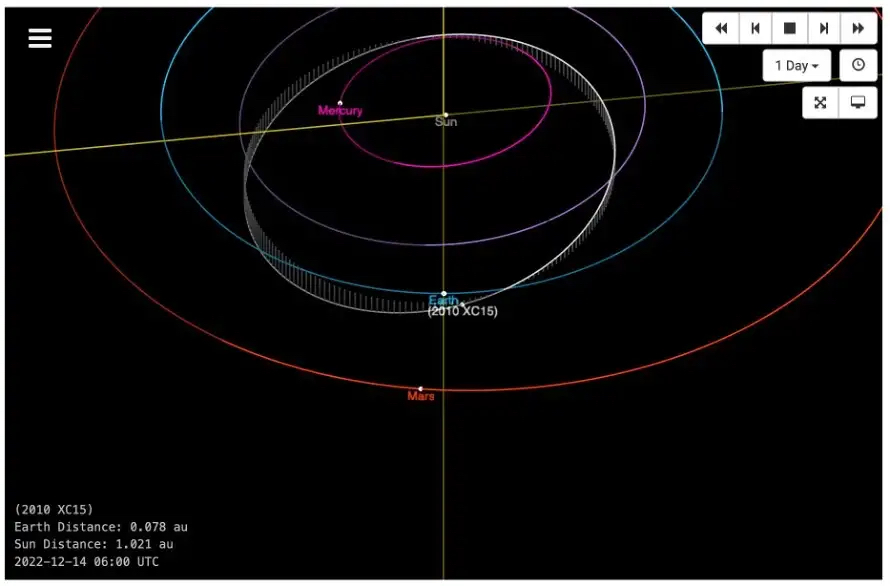

Using a powerful transmitter, the experiment sent long wavelength radio waves into space for twelve hours, targeting a small asteroid cataloged as 2010 XC15. Discovered by the Catalina Sky Survey back in 2010, this asteroid is about 150 meters across and is considered a potentially hazardous object as its orbit is mostly within the orbit of Earth. On December 27, 2022, 2010 XC15 passed by our planet at about two lunar distances, allowing the HAARP team to use radio waves to observe the small body during that close approach.

While most programs use optical and radar telescopes to collect data about the orbits and shapes of asteroids, as well as somewhat image their surfaces, these observations use short wavelengths that simply bounce off the surface, providing little to no information about the interiors. The long wavelengths transmitted by HAARP, on the other hand, are capable of penetrating the surface and providing information about the characteristics such as density, similar to how ground-penetrating radar works here on Earth to detect anomalies underground.

HAARP sent the signals up to 2010 XC15, and two radio arrays received the return signals: the University of New Mexico’s Long Wavelength Array and the Owens Valley Radio Observatory Long Wavelength Array near Bishop, California. However, the results are pending, as lead investigator Mark Haynes notes: We will be analyzing the data over the next few weeks and hope to publish the results in the coming months.

Finding new ways to determine the structure of potentially hazardous asteroids like 2010 XC15 and the more infamous Apophis will help scientists understand just how hazardous the asteroids may actually be. If we can determine the distribution of mass inside the asteroid, we can plan out missions that can target the asteroid to change its orbit, as NASA did with the Double Asteroid Redirection Test mission, or DART, last year. The question then becomes what sort of impactor we need to shift the orbit because if the asteroid is a rubble pile like Bennu or Ryugu, an impact could break the asteroid apart. That would potentially result in more impacts, but they would be smaller and likely burn up in the atmosphere.

Automobile-sized asteroids will also generally burn up in the atmosphere, despite creating fireballs in the sky, and they happen about once per year. Meteoroids around 100 meters in diameter hit our atmosphere every 2,000 years or so, and they can cause significant damage. Dinosaur-killing asteroids — on the order of 100 kilometers in diameter — only strike every few million years. While extremely rare, the goal is to prevent such a catastrophic strike. Experiments like the HAARP transmission and the DART mission are the latest steps in the important field of planetary defense.

As an interesting side effect of last week’s experimental transmissions, amateur astronomers and ham radio operators reported to the HAARP program that they also received the transmissions. The chirps were broadcast at “slightly above and below 9.6 megahertz” every two seconds, and, as HAARP program manager Jessica Matthews notes: So far we have received over 300 reception reports from the amateur radio and radio astronomy communities from six continents who confirmed the HAARP transmission.

Per SETI Institute research scientist Michael Busch, who was not involved in the experiment, the signals could be picked up partly “because of the ionosphere scattering most of the beam going out and coming back.” These reports will also help the HAARP team understand the ionospheric conditions at the time of the transmissions. Two experiments for the price of one!

I’m looking forward to the results of this program. After all, I’d really rather not go out like the dinosaurs.

More Information

University of Alaska Fairbanks Geophysical Institute press release

This article was originally published for medium.com.